AMA Victoria made this resource available to members only.

Get access to all of AMAV's articles, events, and more by joining today.

- Access all member-only resources from AMAV

- Dig deeper into the subjects that matter to you

- Get in depth articles to achieve your professional goal

Already a member? Log in

The COVID pandemic has focused much attention on crisis leadership and rightly so. We needed effective responses as the pandemic emerged and then took hold. This has put incredible pressure on leaders at all levels of society and at all levels of organisations. This hasn’t been easy. In fact, it has been – and continues to be – incredibly difficult. Operating in crisis mode for an extended period is exhausting. So, what can we do? What can help us during this time of sustained elevation and vigilance?

Effectively functioning teams not only make leadership more effective, they also spread the load, helping reduce exhaustion and the fatigue that unfortunately will only increase as the pandemic continues. This means that successful leadership comes not only from those in formal leadership roles, but from everyone. Indeed, every Australian is being asked to show leadership now by engaging in new behaviours, new ways of living and working and enacting the new rules of distancing and mask wearing. In this way, effective leadership is distributed and collaborative; characterised by and dependent on our interdependence. We rely on each other and we rely on each of us bringing our best self to the work.

Effective teams are not created out of thin air. They do not occur simply or organically. There are things we can and need to do to cultivate teamwork and create effective teams. Psychological safety is a concept that has much to offer this situation. It is a key aspect of team culture that supports people speaking up, sharing knowledge and acknowledging their mistakes. All of this makes teams more likely to improve and – especially important during these times – learn from mistakes and not repeat them once they have been made.

Psychological safety is the belief that I can speak up and I won’t be criticised or humiliated by doing so [1]. It is an identifiable and measurable characteristic of a team. Psychological safety describes a core characteristic of a climate where people feel they can speak up with candour.

Teams that share their mistakes are able to learn from them. Teams that speak up about mistakes are teams where there is high psychological safety; not having a climate of psychological safety is problematic and risky. If people don’t speak up, if people remain silent with their ideas, their experience and their mistakes, then decision-making is impaired as it is not based on complete information and the learnings that can come from that. In complex work, this is a problem – and the problems can become very large indeed.

New problems demand and create new solutions, but they are rarely perfect in their first incarnation. But improvement can’t occur when new processes and new treatments are not openly interrogated and discussed, when shortcomings and failures are not brought into the light. Without this they can’t be fixed, and the individuals involved cannot be unburdened by the failures that are unlikely to be theirs alone.

Importantly, psychological safety is something that we can cultivate in our teams. There are things we can all do to create this climate in our teams each day.

And while leaders have a clear role to play in cultivating psychological safety, all of us can demonstrate good leadership by acting in ways to create, promote and sustain psychological safety in the groups and teams we work in. This means acting in ways that allow people to speak up with candour, without fear of humiliation or punishment.

Amy Edmondson and her colleagues have spent almost two decades researching psychological safety – how to measure it, how to cultivate it and how it contributes to effective teamwork. In her most recent book The Fearless Organisation, Edmondson suggests leaders can do three things to create psychological safety in the workplace:

- Frame the work as a learning problem not an execution problem (uncertainty and possibility of failure and part of the work)

- Acknowledge your own fallibility

- Model curiosity by genuinely asking for input and responding appropriately.

Framing the work – or setting the stage – is about approaching the situation the team is facing as a learning opportunity rather than a bounded task to accomplish. For example, if a leader of a crisis response wanted to reduce people’s fear of failure and making a mistake, she or he might say something like, “We are going to make mistakes – it’s unlikely we’re going to get this completely right the first time we try – so let’s tell each other as soon as we suspect something’s not working”. This helps to frame the work as complex and uncertain and opens up the nature of the work required to include asking questions, voicing concerns and ideas, rather than following instructions.

When the leader acknowledges their own fallibility, this role models humility – an awareness that you don’t have all the answers, have shortcomings and make mistakes. This is a very powerful way to engender psychological safety in the team. For example, a leader might say, “At the moment, I think that this makes sense, but I don’t know, what do you think?”, or “At first I thought that this was the best course of action, now I don’t think it was and I am sorry for that”.

Modeling curiosity is about leading through inquiry. Being genuinely curious about the work, means engaging more members of the team so that they feel comfortable participating in the process. This can include asking questions and finding out more, being interested in what other people think and taking the time to listen to what they say – not interrupting, not talking over, not dismissing their suggestions too quickly.

So that’s the theory. What might this look and feel like in your day-to-day work?

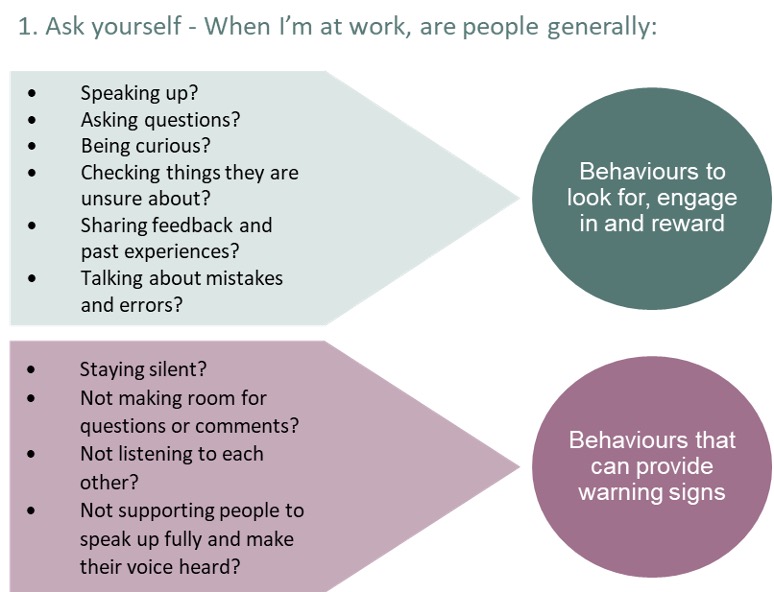

First, assess the situation: what can I observe as indicators of the presence and absence of psychological safety, in myself and in others?

In a practical sense, not supporting people to speak up fully and make their voice heard could be seen in people not being comfortable about being themselves and speaking up about their experience. This can be very often be a surprise and a shock to leaders and managers and unfortunately it is very common. Indeed, as humans we are very self-conscious and dread the thought of making a mistake in public. So, the leaders’ role is to help communicate the expectations for the team climate – to say, “It’s ok to share what you think and even what’s not working … I actually want to know so I can make it better (not so that I can punish you or give you a bad review)”.

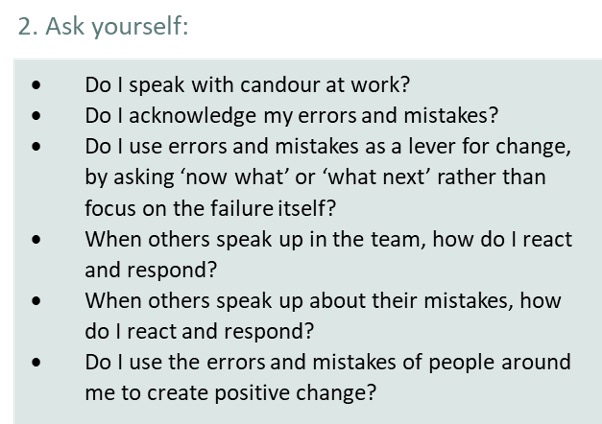

Second, consider the words and actions you can use to create psychological safety.

Let’s now take this further into the practice of leadership to consider the types of words and behaviours that create psychological safety. These are the behaviours and practices that leaders can take up to create more effective teams and cultivate a climate of psychological safety.

- Frame and introduce the next piece of work in a way that acknowledges its complexity and uncertainty. And include a statement about how mistakes and new directions are very likely – indeed inevitable in current circumstances

- Directly invite people to participate in meetings and discussions to share their thoughts – for example by inviting everyone to take their turn to share their thoughts, by thanking people when they do speak up, and ensure that you do actually listen to the contribution and respond appropriately, ensuring that you are showing it is a safe space.

- Talk about your own mistakes, failures, and limitations. This does not mean speaking at length about past mistakes, perhaps even a simple statement that you have made mistakes and understand that it is part and parcel of complex work – it is inevitable in healthcare.

- Show how you learned from them – this is about modelling this learning frame; that being open about mistakes and errors allows everyone to learn from them.

- Ask powerful questions; questions that allow the possibility for people to speak up (for example, a question that you are truly interested in and curious about, a question you don’t have an answer to, and one that is genuinely related to improving work.

- Listen and respond in a way that shows you listened and that you are interested in looking at ways to use what was shared to contribute to improvements in the work.

- Don’t stigmatise or punish mistakes and risk-taking – start talking in a way that creates this as a learning opportunity – what does this mean for what’s next and how we make sure we do better next time this situation confronts us (note that clear violations should be called out and punished)?

- Ask for feedback – this is a great technique for promoting engagement and people contributing to discussions and feeling safe. Directly ask people what they think and state that they can let you know anytime and by other means (perhaps one-to-one or over email if that is an easier first step).

While this sounds simple, it’s not necessarily easy. These individual leadership behaviours are easy to write about, but they are not easy to do. They are skills and like all skills they require learning, practice, and conscious refinement. But as I hope to have illustrated above – they can be broken down into small, doable steps, many of which can provide a useful stating point. Go gently, and good luck!

Dr Anna Clark, PhD

Leadership consultant and coach

POSTCRIPT: Interestingly, the origins of this decades long program of research are in healthcare settings. Specifically, teams of nurses were studied. The topic of interest was the reporting of medical errors. Amy Edmondson talks about this work in her articles, books and TEDTalk. For more on this topic see especially – Teaming; The Fearless Organisation. Her TED talk and other popular presentations can be found via her website at HBS.

[1] Edmondson, A. C. (2012). Teaming: How organisations learn, innovate and compete in the knowledge economy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, and Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The Fearless Organisation. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.