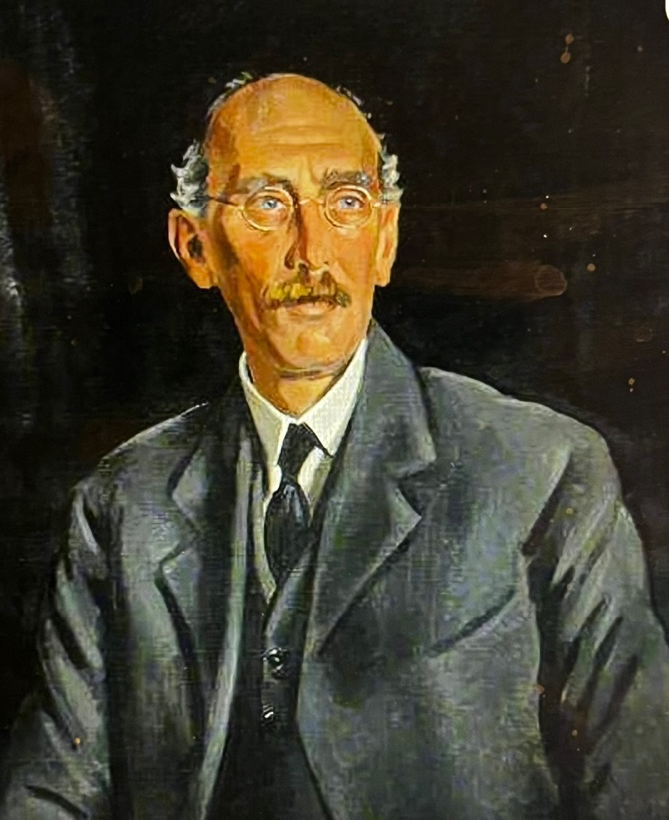

Image: Painting by Edward Morland Lewis (1903-1943) The Royal Society London. Gift from Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine 1980. Painted in 1930.

Image: Painting by Edward Morland Lewis (1903-1943) The Royal Society London. Gift from Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine 1980. Painted in 1930.Sir Charles James Martin (1866-1955) Kt, C.M.G., F.R.S.

M.B., B.Sc. (Lond.), M.D., D.Sc. (Melbourne.), Hon. D.Sc. (Sheffield.et Dub.), Hon.

LL.D. (Edin.), Hon. D.C.L. (Durham.), Hon. M.A. (Cambridge), F.R.C.P.

There is little to read of anything extraordinary that Dr Charles Martin did in his 1901 presidency of the Medical Society of Victoria. His contribution to Australia’s and to the World’s Science exceeds expectation and certainly overwhelms his Medical Society of Victoria presidency.

The most outstanding legacy today to AMAVictoria is his memorabilia of his personally designed sphygmomanometers in the AMA collection gifted to the Medical Museum University of Melbourne in 2011.

Charles James Martin was an adventurous young man. He was born in 1866 into a middle class blended family of many children whose father was an actuary. They lived in an old Georgian House on the outskirts of London. Early in his life he was exposed to a doctor’s life. His uncle Dr Francis Buckell had a country practice in Hampshire. Charles often spent holidays with him and would go on patient rounds in the pony cart experiencing medicine at the “grass roots.”

Initially mathematics was his challenge but one day he found this little book below which changed his life.

He lived in Australia for less than 15 years around the turn of the century, but his name lives on. Search any website associated with science scholarships offered in Australia today and you will find his name. Notable Australian and overseas scientists have been awarded the National Health and Medical Research Council C J Martin Scholarships since 1951.

He lived in Australia for less than 15 years around the turn of the century, but his name lives on. Search any website associated with science scholarships offered in Australia today and you will find his name. Notable Australian and overseas scientists have been awarded the National Health and Medical Research Council C J Martin Scholarships since 1951.

With the nomenclature of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in education today, young Australian students should visit the history of this man and strive to achieve his academic prominence.

When his family did not support his interest in Medical Science, he set about finding his own direction. He challenged his family to allow him to pursue his dream if he was the “best”. His initial endeavour was to do a Bachelor of Science at the University of London gaining a gold medal and a financial scholarship of 50 pounds a year for two years in physiology. He succeeded and his family relented.

Using this money, he travelled to Leipzig in Germany to work with the Carl Ludwig who was an early notable in science and experimentation in physiology.

After his return to England, he was employed as a demonstrator at King’s College and then completed his medical studies at St Thomas’s Hospital. After graduation he looked for further challenges.

On hearing the pay was better in Australia, he travelled there in 1891 soon after his marriage to Edythe Hart Cross to take up a position at the University of Sydney as a demonstrator. His reputation grew with his work not only in Australia but overseas. In 1897 he moved to the University of Melbourne and in 1901 became the Professor of Physiology.

His early work in Australia revolved around teaching and developing research departments in Universities concentrating on infectious diseases, sanitation and hygiene. In his spare time, he enjoyed bush expeditions around Sydney, Melbourne, New Zealand and Tasmania. It is said he even took a “holiday with pay” as a locum for a “up country” doctor!

He loved the Australian countryside. It was not just a place for relaxation and pleasure; he was never a thought away from his love of science. He was enamoured by Australian fauna: working to find the formation of antibodies to Black and Tiger snake venom; looking into the anatomy, metabolism and heat regulation of monotremes Platypus and Echidna and later working on Myxoma virus to rid Australia of the rabbit infestation.

In 1898 in Melbourne the University had financial issues with little money available for research. This did not bother him too much, he just sought an alternate method by designing, building and encouraging others to make equipment as required and pursue their scientific investigations.

One of his foremost inventions was to measure arterial blood pressure. He devised a portable, but sufficiently accurate instrument, which was the forerunner of today’s sphygmomanometer: hence the acquisition of the original pieces in the AMA Victoria collection.

The diversity of his interest and skills was endless.

Dr Charles Kellaway who was the director of WEHI (1923-44) wrote of him

“Martin had gifts which made him specially capable of carrying out first rate research under adverse conditions, and not short of time, money, equipment or technical help could inhibit him. His mechanical ingenuity and resource surmounted all difficulties and his wide interests and equally wide knowledge, his strong critical facility, and the fact that he was always eager to learn from anyone, however humble, who had any special knowledge, made him an ideal worker in a young country. His enthusiasm was infectious, and both in Sydney and Melbourne he found disciplines and co-workers.”

His moved back to England in 1903 to head the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine where he continued with various projects. He travelled to India to investigate and research the Bubonic Plague and Typhoid Fever. Worked with Dame Harriette Chick, a British Microbiologist, devising the Chick-Martin Equation for defining the effectiveness of disinfectants. Both Charles and his staff worked on the mechanics of disinfection, heat coagulation and the precipitation of proteins. His endeavours into human nutrition involved vitamin deficiencies such as Beri Beri and Pellagra.

Despite his involvement with many projects his name was often left off papers written, never claiming personal kudos. Professor Henry Priestley, biochemist, academic and physiologist said, “Very much of his best work was hidden.” Priestley recalled whilst working at the Lister Institute with Martin, that “Afternoon Tea” was mandatory for staff. It was a place of discussion and learning just as much as working in the laboratory.

He was known to have put down as a hobby “tinkering”! He was a great teacher having a unique capability of describing scientific work in simple terms. Kind words described him “never idle, never in a rush”, “soul of kindness and courtesy”, “completely unboastful and modest.,” although he was also known not to suffer fools gladly.

In the era before computerisation, it was said he had a phenomenal system of filing and could find relevant pages from his library at the drop of a hat! In his Obituary in Nature, it was said “he had not the inclination to waste time on the elegancies of dress, and on more than one occasion had - but only for a moment – been mistaken for a wandering tramp”

In early 1951, The Medical Journal of Australia contained an article The Fifty Years of Medical Research in Australia. A copy was sent to his home in Old Chesterton in Cambridge. He responded soon after and the following is an extract of his letter.

“I read with pleasure reminiscences of many old colleagues and co-operators in trying to build up a real scientific medical profession in Australia. The material was first rate. The quality of the medical student was superior to what I had been used to teach in London. They all meant business, and the experimental method of approach came naturally to them and intellectual adventure was congenial. A drawback for the time being was that the best of them scorned research scholarships after graduation and came to Great Britain or the U.S.A. and were induced to stay. This drainage of some of the best talent was a menace to Australia.”

His fondness for Australia continued when his enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force 3rd General Headquarters in World War One. At demobilisation he had the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He served as a pathologist / bacteriologist in Egypt, Lemnos and Rouen. K. F. Russell in his book Melbourne Medical School records his research in Lemnos with enteric fever and his recommendation to inoculation troops with a vaccine containing parathyroid and typhoid bacilli. Australian troops received T.A.B vaccine some time before it was used in the British Army. In Egypt he was asked to investigate heat exhaustion in the desert together with the providing adequate fluids to servicemen. For his war service he was mentioned in Despatches twice.

He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1923 and awarded the Companion of Saint Michael and Saint George (Knight Bachelor) in 1927.

Sir Charles's interest in Australia remained unabated. Over the years he was very cooperative with Australian Universities offering places at the Lister Institute for Australian scientists to further their skills. One of these Australian scientists was Frank McFarlane Burnet who gained his PhD after studying with Martin. He went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1960.

After Charles retirement in 1930 from the Lister Institute, he did not entirely retire. At the request of the Australian Government, he investigated a number of problems concerned with the health and economy of Australia. There were many roles too many to record here. Two of note were the Chief of the Division of Animal Nutrition at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) at the University of Adelaide and a scientific advisor to the International Wool Secretariat looking into sheep nutrition and wool production. He revisited Australia on a number of occasions and renewed his old friendships and established many new connections.

During the Second World War, he continued to support the military cause as a private citizen through the Lister Institute and Cambridge University. His home Roebuck House in Old Chesterton Cambridgeshire became his “laboratory”.

He survived his wife Edythe by one year. Their daughter Maisie who was born in Melbourne was also a bacteriologist. His grandson Martin Gibbs allowed 40 years of family diaries and war notes to be used in a more recent book written by Patricia Morison called The Martin Spirit: Charles Martin and the Foundation Science in Australia.

Charles James Martin died in 1955 and is buried in the Parish of Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge.

His successes and extensive contributions to Australian science have been somewhat forgotten.

AMA Victoria is honoured to write about this great man who was the President of the Medical Society of Victoria in 1901.

Charles James Martin biography has been written by Dr Jean Douglas. Information has been obtained from Medical Journal of Australia, University of Sydney and University of Melbourne, K F Russell Melbourne Medical School, Lister Institute, Journal of Nutrition Wellcome Collection, Roebuck House Old Chesterton, Katrina Hedditch Lemnos 1915 A Nursing Odyssey to Gallipoli Robert Likeman Gallipoli Doctors, Trove, National Archives of Australia.

DOWNLOAD ARTICLE